Halfway Pond Conservation Area in Plymouth. Photo by Jerry Monkman.

By Zoë Smiarowski, Stewardship Programs Manager

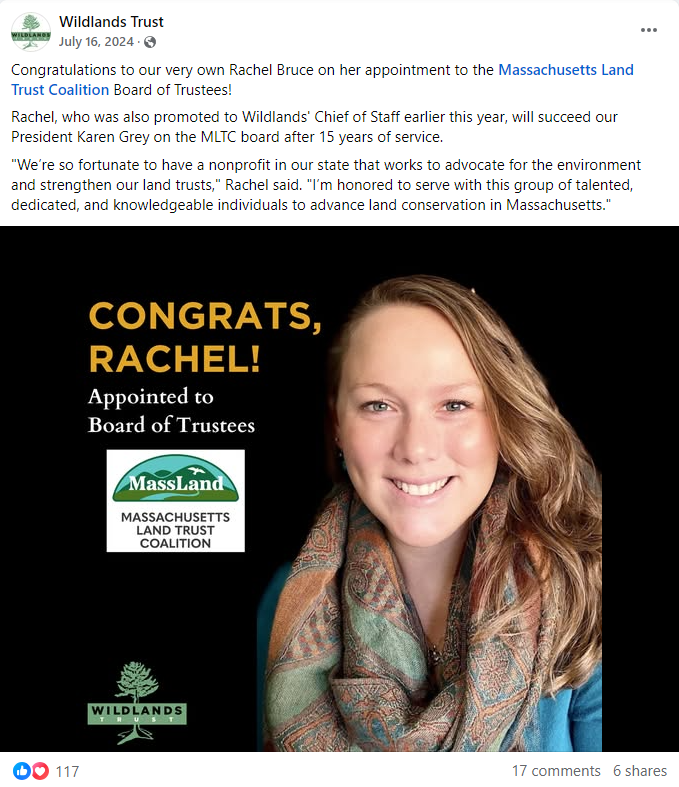

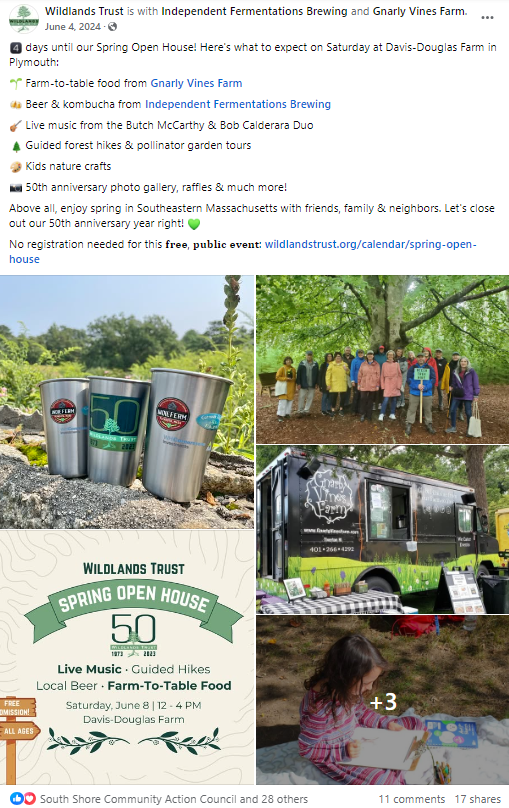

Once a hiking trail is established, many may consider the job done. But few realize the consistent care required to keep a preserve beautiful and safe for people and wildlife. The Adopt-a-Preserve (AAP) program is one of the key ways that Wildlands can manage to maintain 14,000 acres of conservation land across the region with a stewardship staff of just three!

Volunteer trail monitoring through AAP peaked during COVID, as people sought ways to get outside and give back to the community during a time of uncertainty and isolation. Since then, the AAP volunteer base has steadily declined. But the benefits of adopting a preserve—for you and for local conservation lands—have never been greater!

What is AAP?

Adopt-a-Preserve is Wildlands’ flagship volunteer program, established to connect outdoor recreationists who may already be out walking our trails with a meaningful way to give back to their favorite (or even a newly discovered) preserve!

Here’s how it works:

Interested volunteers pick a preserve typically within a 15-minute drive of their home or work (or anywhere else they spend their time!). A Wildlands staff member or seasoned volunteer will meet you on site to go over the basics of monitoring and discuss a range of ways AAP volunteers can help with passive or active trail maintenance. Then, volunteers commit to sending in at least one report per month detailing what they observed and if they did any work on the trail. Afterwards, Wildlands staff reviews the report, assessing any pictures of downed trees, vandalism, or anything else that may have come up at the visit. The report enters the Wildlands database in the Landscape software to document observations on the property over time. Finally, if there are any issues to follow up on, Wildlands staff will plan a site visit to address them!

Cortelli II Preserve in Plymouth. Photo by Jerry Monkman.

Do AAP volunteers really make a difference?

Yes! Our stewardship staff is small, so your monthly visits can go a long way toward ensuring our preserves stay in good shape year-round. Even reports that let us know the preserve is in good shape help provide us with a frame of reference if problems do come up and can also help us prioritize tending to properties that haven’t had eyes on them as recently.

AAP participation might have declined since COVID, but the program still made a significant impact on our stewardship capacity in 2024: 57 AAP volunteers filed 272 reports, providing coverage for 8,300 acres of conservation land!

Okay, I’m in! How can I help?

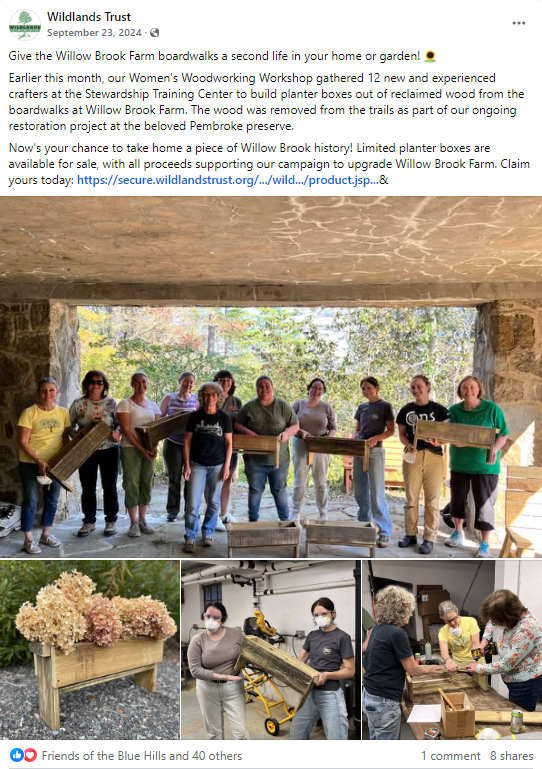

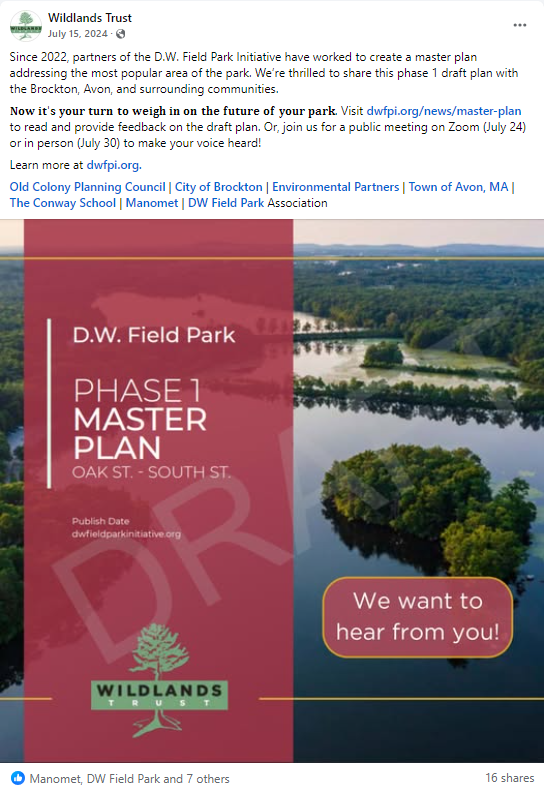

You can make a difference at any preserve, but the following preserves are in particular need of volunteers’ watchful eyes:

Tucker Preserve/Indian Head River Trail (Pembroke)

Hoyt-Hall Preserve (Marshfield)

Great Neck Conservation Area (Wareham)

Willow Brook Farm (Pembroke)

The Nook (Kingston)

Phillips Farm (Marshfield)

North Fork Preserve (Bridgewater)

Crystal Spring Preserve (Plainville)

South Triangle Conservation Area (Plymouth)

Halfway Pond Conservation Area (Plymouth)

Emery Preserve (Plymouth)

Thank you for your consideration! To learn more, visit wildlandstrust.org/volunteer or contact Stewardship Programs Manager Zoë Smiarowski at volunteer@wildlandstrust.org.